British Footballers As Cold Warriors

01/01/2024 - 12.00

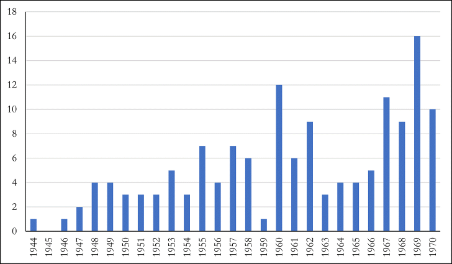

Dion Georgiou

Footballers’ autobiographies emerged as a subgenre in Britain in the wake of the Second World War, turned out by relatively recently established, London-based publishing companies developing a niche in sports and leisure-focused books, such as Nicholas Kaye and Stanley Paul. Eddie Hapgood’s Football Ambassador was published in 1944, followed by Tommy Lawton’s Football is My Business, in 1946. These became increasingly frequent, as the table below demonstrates [1]. From 1947 to 1958, at least two further works of life-writing ostensibly authored by current and former players and managers appeared annually, before a spate of 27 between 1960 and 1962, and a further flurry of 46 between 1967 and 1970. A large degree of caution is necessary in attributing authorship of these books, as they were primarily ghost-written by sports journalists. Nonetheless, we ought to recognise footballers’ agency within them, both as economic benefactors from their production, amid limits on their existing sources of income, and as protagonists in the ‘real-life’ events described within them.

Encounters with Eastern European Football

The exoticism of encounters with overseas teams and of sojourns abroad meant such encounters were given pride of place, and often dedicated chapters, in these books. Through to the late 1950s, this was particularly the case with Eastern Bloc sides, given the mystery and intrigue such episodes involved, as well as the prominent place of events such as Dynamo Moscow’s 1945 tour of Britain and England’s 1953 and 1954 defeats against Hungary in the game’s mythology. These narratives usually hinged on binary representations of differences between Western and Eastern political economies, both in footballing and broader terms. Representations of Eastern European footballing culture were shot through with Cold War stereotypes, albeit while also incorporating older British/European binaries.

Much that was positive focused on apparent infrastructural advances by communist sporting regimes. Billy Wright’s 1957 autobiography, Football Is My Passport commented on Dynamo Moscow’s stadium’s ‘capacious and airy’ changing rooms, with ‘the novelty of deep and roomy armchairs’ – comments echoed in Kelsey’s Over the Bar [2]. Johnny Haynes’s 1962 book It’s All in the Game, meanwhile, said of the Nepstadion in Budapest that ‘...The dressing-rooms were furnished with armchairs, bowls of fruit and occasional tables, carpets on the floor and record players. This was very civilised and an intelligent contrast to our bleak and spartan dressing rooms at home, some of which were downright shabby.’ [3].

Yet other characterisations of Eastern Bloc sporting political economies tended to incorporate more negative Cold War stereotypes. Harry Johnston’s The Rocky Road to Wembley, for example, reassuringly reiterated the British footballer’s inherent superiority, claiming ‘...There was no one in that Hungarian forward line who could, as an individual player, trick you with the ease of [Wilf] Mannion, [Jimmy] Hagan, [Len] Shackleton, [Tom] Finney or [Stanley] Matthews’ [4]. Other autobiographies were far more positive about the Hungarians, albeit while refusing a narrative of collectivism trumping individualism. Johnny Haynes’s Football Today insisted Hungary had displayed ‘...no slavery to a rigid tactical plan drawn up by a backstage mathematician, but a fluency and elasticity in which the imagination of the individual artist is given full rein’, explaining that while tactics were important, it was also vital for systems to suit players, not vice versa [5].

Characterisations of the Soviet team, who England faced four times in 1958, were far less positive. Finney on Football, published that same year, asserted, ‘...I do not think the Russians are natural footballers’, but had rather been ‘taught’ to play the game and become ‘proficient’ at it, though it warned that they ‘are taking such an active interest in sport that it would be well not to underestimate their capabilities…anything tackled by Russia is usually done well.’ [6]. Published four years later, Haynes’s It’s All in the Game reminisced that ‘...we made a startling discovery about the Russians. We discovered that they were not supermen from outer space armed with some secret weapon that made them super footballers…They were in short human, and on the day, not terribly good footballers.’ [7].

Autobiographies also contained mixed assessments of and responses to communist models of sporting administration. After the Hungary defeats, there were calls in the English sporting press for a reorganisation of professional football in line with the more centralised approach adopted by their vanquishers. The Rocky Road to Wembley, however, ridiculed the prospect of appointing a ‘Minister of Sport’ or ‘Soccer Führer’, just because ‘...the Hungarians work on this principle and other foreign teams do likewise’. It likewise gave short shrift to suggestions they should adopt the Hungarian model of selecting the cream of the nation’s footballers and keeping them together to play in internationals, insisting instead on an organic set-up where the emphasis remained on league football, which it described as ‘...English soccer for the masses’. [8].

Finney on Football was more cynical about ‘...the ninety-two alleged top-class teams in the Football League’, but conceded that the diffusion of talent between them rendered the Hungarian team selection process inimitable [9]. I Lead the Attack, striking up its favoured theme of the incompetence and greed of the game’s administrators, warned ‘...Soccer bosses’ that ‘...Britain’s Soccer prestige…is in grave danger of being damaged beyond repair’. It advocated that they select all-British sides for matches against overseas opposition and shorten the league season to give these players time to train and gel together; ‘...Then let this team loose amongst the tip-top Continental boys. They would whip them so thoroughly that Hungary would assume her old role – as the place the rhapsodies come from.’ [10].

Communism in British Footballers’ Autobiographies

Incursions of political objectives into the sporting sphere attracted especial opprobrium in footballers’ autobiographies. Whereas Tommy Lawton’s Football Is My Business and Stanley Matthews’s Feet First, published in the late 1940s, praised the Dynamo team they encountered in 1945 as footballers and sportsmen, later accounts of the tour were subject to significant Cold War revisionism. Cliff Bastin Remembers piled on stereotypes in describing their alleged conduct during the Arsenal match, describing their claim the Arsenal side they faced was virtually an England representative team as ‘...comparatively mild’ compared with ‘...subsequent distortions of fact by the Kremlin’, for example [11].

Scotland and Glasgow Rangers player George Young’s autobiography, Captain of Scotland, claimed the Dynamo players had not mingled with Young and his teammates at their post-match reception, and ‘...politely made it clear they did not understand they did not understand what we were talking about when we approached them, all the time casting their eyes in the direction of their officials’ [12]. Ford’s I Lead the Attack called them ‘...a pretty-pretty side that didn’t want to be bumped’, accusing them of making ‘political capital out of a game that had been Britain’s pride and joy’; Ford, it should be noted, had not played against Dynamo during their tour [13]. This theme persisted in later accounts. Cliff Jones’s Forward with Spurs, while conceding that the Katowice stadium of Polish team Gornik Zabrze, who Tottenham had faced in the European Cup, was impressive, added that ‘...As with all Iron Curtain country stadiums a great deal of money and planning had gone into its erection − a policy, I suspect, based on propaganda.' [14].

Accounts of visiting Eastern Europe, meanwhile, typically depicted life there as austere, illustrated through comic anecdotes. Over the Bar contained an account of the Wales team’s trip to Leipzig, during which, noticing the players eating chocolate, a crowd gathered around them to ask for some, until the police came along and dispersed them [15]. Finney on Football included a chapter entitled ‘A Preston Lad Looks at Moscow’, describing Finney’s recent visit there with England. It noted that ‘...the private shopkeeper apparently does not exist in Russia’, claiming that ‘They are not at all well-dressed as a nation’, while hankering after Britain’s ‘admittedly vulgar, yet always colourful, advertisements’, ‘...the bright blues, greens and pinks of the modern motor-car’, and ‘...the neon lights of cafés and restaurants’ [16]. Cliff Jones’s Forward with Spurs likewise described Katowice as ‘...a grey place still showing the scars left by heavy bombing’. It noted that there were very few shops there, the quality of goods available was poor, and people wore ‘drab’ clothing, while describing the club’s accommodation as uncomfortable, with hard, flea-ridden beds [17].

Such narratives emphasised the superiority of British life, making implicit and explicit comparisons with growing affluence enjoyed back home, and continued the advocacy of capitalism visible elsewhere in the books. By contrast, Billy Wright’s Football Is My Passport utilised his 1954 trip to Hungary as a prism for criticising affluence’s impact upon Britain and its football. It claimed that ‘...Hungary resembles Britain from 1920 until about 1936’, in that ‘...Everywhere you go you see small boys kicking balls about’, because they had ‘much fewer methods of entertainment than we do in the western world. Television, radio and cinemas do not take from the playing-fields youngsters in the number these entertainments do in Britain’ [18].

Footballers’ autobiographies were also regularly critical of communist political systems. Finney on Football castigated the ‘...state of the state-controlled mind’ in Moscow, where no one accepted tips and interpreters spouted communist doctrine ‘...from the book’. Finney’s unpretentious Lancastrian honesty was contrasted with the restrictions of speech and false rhetoric he encountered in Moscow, as was that of another England player, Tommy Banks. At one point, apparently, Banks tired of being told by the interpreter about the good the Soviets were doing elsewhere in the world and countered, in ‘...typical down-to-earth Lancashire fashion’: ‘...Ay, that’s all very well, but what about Hungary!’ [19] All in the Game also recalled Banks disputing with the interpreter, who always wore the same old sports coat, ‘...and Tommy used to say how marvellous communism was, when you didn’t have a change of clothing’ [20].

Players’ autobiographies also represented a culture of fear in the Eastern Bloc states they visited. John Charles’s King of Soccer described the Leipzig crowd for Wales’s 1957 World Cup qualifier against East Germany as the quietest he had ever played in front of, and queried whether ‘...the strange (to us) political system has had its effect on them’ [21]. It also claimed the Czechoslovak side Wales had also faced in qualifying ‘...all look so solemn and suspicious…Everyone appears to be frightened of everyone else, and [at the post-match banquet] no one would even accept a British cigarette’ [22]. Similarly, Bobby Charlton’s Forward with England expressed a dislike of Belgrade, as ‘...there are too many policemen and soldiers for my liking and one always has the feeling you have to be careful what you do and what you say’, while also remarking on the ‘...watchtowers manned by guards with guns and searchlights’ he had witnessed in Czechoslovakia [23]. These accounts thus extolled political, as well as economic, freedom, as central to western superiority.

Yet emphases on unfamiliarity and repressiveness of life under communism comingled to varying degrees with expressions of personal apoliticism and affinity and friendship across political borders, particularly within the sporting sphere. Wright’s Football Is My Passport -remarked that the Wolverhampton Wanderers players had received ‘...a magnificent welcome’ on their 1955 trip to Moscow, and that the Dynamo players ‘...accepted us as soccer ambassadors and friends’ at the post-match banquet. Wright’s autobiographies were relentlessly tactful, but there were echoes of this stance in books otherwise far more openly critical of communism. Finney on Football featured a photograph of Finney readying for training in Moscow while watched by three young boys, captioned ‘...Kids are kids the world over’ [24]. Nearly a decade later, Forward with England stressed sport’s unifying power of sport, even while perpetuating its critique of life under communism:

'When I come off the field in say, Moscow or Warsaw, I can talk seriously to a player who leads a completely different life to me. The only subject which is taboo is politics. I can never say what I am thinking: ‘Your country’s in a depressing state – if you were playing in England you would be earning a lot more money for you and your family.’

The book insisted Charlton would ‘...have nothing to do with politics generally’, professing he found it ‘...too deep a subject’; rather, ‘...I just pay my tax and forget it’ [25]. Such passages extolled traditional ideals of sportsmanship, with footballers’ star statuses tied to notions of their being role models, as well as sentiments of universalism and pacifism alongside acceptance and reinforcement of East/West binarism, and demarcated football as a field in itself, separate from the world of high politics.

References

1. Based on analysis of data contained in Richard William Cox, British Sport: A Bibliography to 2000. Vol. 3: Biographical Studies of British Sportsmen, Sportswomen and Animals (London: Frank Cass, 2003); and Peter J. Seddon, A Football Compendium: A Comprehensive Guide to the Literature of Association Football (London: British Library, 1995).

2. Billy Wright, Football Is My Passport (London: Stanley Paul, 1957), p. 111; Jack Kelsey, Over the Bar (London: Stanley Paul, 1958), p. 84.

3. Johnny Haynes, It’s All in the Game (London: Arthur Barker, 1962), p. 56.

4. Harry Johnston, The Rocky Road to Wembley (London: Museum Press, 1953), p. 59.

5. Johnny Haynes, Football Today (London: Arthur Barker, 1961), p. 45.

6. Ibid., p. 108.

7. Haynes, It’s All in the Game, p. 107.

8. Johnston, The Rocky Road to Wembley, pp. 56–57.

9. Tom Finney, Finney on Football (London: Nicholas Kaye, 1958), p. 76.

10. Trevor Ford, I Lead the Attack (London: Stanley Paul, 1957), p. 57.

11. Cliff Bastin, Cliff Bastin Remembers: An Autobiography (London: Ettrick Press, 1950), pp. 165–173.

12. George Young, Captain of Scotland (London: Stanley Paul, 1951), pp. 25–26.

13. Ford, I Lead the Attack, p. 57.

14. Cliff Jones, Forward with Spurs (London: Stanley Paul, 1962), p. 174.

15. Kelsey, Over the Bar, p. 122.

16. Finney, Finney on Football, pp. 30–31.

17. Jones, Forward with Spurs, p. 173.

18. Wright, Football Is My Passport, p. 45.

19. Finney, Finney On Football, pp. 24, 29–32.

20. Haynes, All in the Game, p. 91.

21. John Charles, King of Soccer (London: Stanley Paul, 1957) p. 117.

22. Ibid., p. 118.

23. Bobby Charlton, Forward for England (London: Pelham, 1967), pp. 55, 96.

24. Finney, Finney on Football, illustrations between pp. 16 and 17.

25. Charlton, Forward for England, pp. 96–97.

Biography

Dr Dion Georgiou is a modern and contemporary historian, primarily of Britain and the US, but within a more broadly comparative, global, and interdisciplinary framework. He writes on the Cold War, and other topics, for his Substack newsletter, The Academic Bubble.

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/240624-Alumni-Awards-2024-Resized.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-18-19/220325-Engineers_teach_thumbail.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/240627-UN-Speaker-Resized.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/240320-Uzbekistan-Resized.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/240229-The-Link-Resized.jpg)

/prod01/wlvacuk/media/departments/digital-content-and-communications/images-2024/240627-Lady-Aruna-Building-Naming-Resized.jpg)